by Amy Flick

Foreign and International Law Librarian, Emory University School of Law

One of the outstanding programs at the IALL 2025 Annual Course in Houston was on the Houston Mutiny and Riot, where African American soldiers stationed at Camp Logan—responding to local harassment, police violence, and rumors of a white mob descending on the camp—marched on Houston on August 23, 1917. This led to the deaths of 15 whites and three African American soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry, also known as the Buffalo Soldiers. 118 soldiers were court-martialed in three trials. The first trial is considered the largest murder trial in U.S. history, with 58 enlisted men tried, and 13 sentenced to death—and hanged the following morning. In two more trials, 52 additional soldiers were convicted and six more were executed.1 The trials were all noted for their lack of due process, even though they met the procedural standards of the Articles of War then in effect.

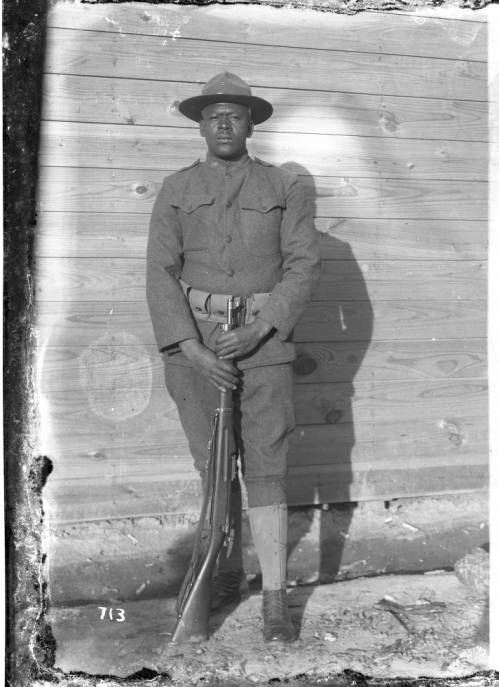

Photo of an unidentified Buffalo Soldier, Houston History Research Center item no. MSS0286-0112. Used with their permission.

Professor Debbie Harwell of the University of Houston began the program, setting the stage for the Camp Logan incident. Her presentation included several photos from the archives of the Houston History Center and from the National Archives. She described how soldiers of the 3/24th had reason to be on edge. African American soldiers of the 25th Infantry had been accused of murder in Brownsville in 1906, leading to 167 being dishonorably discharged.2 Lynchings were on the rise in the early 20th century, including one in Waco in 1916 which drew an estimated 10,000 white spectators. In July of 1917, riots in East St. Louis resulted in the murder of hundreds of African Americans.3

Despite the Chamber of Commerce’s assurances that the troops of the 3/24th would be welcomed, local police were known to the local African American community for their brutality. Conflicts arose between local whites and troops who were not sufficiently “deferential,” including disputes over “whites only” seating on streetcars.4 African American soldiers not on guard duty were disarmed to placate the white residents, and the guards were told to call on the local police if they needed to make arrests.5

Racial tensions boiled over on August 23, 1917, as 3/24th soldier Private Edwards intervened to help an African American woman being mistreated by the police, and he was pistol whipped and arrested. When Camp Logan guard Corporal Baltimore inquired about Pvt. Edwards, he too was pistol whipped and shot at before being arrested. A false rumor reached camp that Cpl. Baltimore had been killed and that a white mob had formed to march on the camp. Between 75 and 100 soldiers led by Sergeant Henry retrieved rifles and marched towards Houston. After three hours of shootings and chaos, with some soldiers returning to camp and others hiding in local homes, three soldiers (including Sgt. Henry) were dead, as well as 11 white civilians and 4 police officers; another 21 civilians were wounded.Houston was placed under martial law and the 3/24th was sent to New Mexico and the review of a Board of Inquiry.6

Colonel Terri Zimmermann, a Judge Advocate in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, picked up the account from there to discuss the courts-martial. Three military tribunals were held at Fort Sam Houston, with 118 men charged under the Articles of War in the cases of U.S. v. Nesbit et al., U.S. v. Washington et al., and U.S. v. Tillman et al. Only one counsel, Major Harry Grier, was assigned to represent all the accused, and he was not a lawyer. He was appointed in October for a trial beginning November 1, did not get the pre-trial records or ask for a delay, and agreed to the pre-trial stipulation that events before the incident were not relevant. The prosecutors relied on the accounts of soldiers who were offered clemency.7

U.S. v. Nesbit —the first trial of 63 soldiers— resulted in 5 acquittals, 13 death sentences, and 45 imprisonments. The verdict was not announced until after the 13 men sentenced to death had been hanged near Camp Travis on December 11, 1917. The other trials, U.S. v. Washington and U.S. v. Tillman, concluded with 16 more death sentences, 36 imprisonments (of which 12 were life terms), and 2 acquittals.8 There was popular outrage when the convictions were reported, and a delegation of the NAACP went to the White House to present a petition signed by 12,000 persons to President Woodrow Wilson, who commuted ten of the later 16 death sentences to life in prison.9

Col. Zimmermann laid out the flaws in the prosecutions and the violations of due process principles that were the bases for the 2020 clemency petition. There were too many soldiers court-martialed in only three trials; the trial started too quickly; there was a lack of a zealous defense, serious concerns about guilt, and no independent post-trial review. The sentence for the first death penalty convictions was carried out much too quickly and in secret. There were also due process issues with the Articles of War at the time, even for courts-martial that met their standards—these included the use of military officers as factfinders for enlisted accused;10 allowing 13-member panels to proceed with as few as five members;11 only requiring a majority to convict (⅔ for capital cases) rather than unanimous assent;12 no requirement that counsel for the accused be a lawyer;13 no requirement of a delay between charging and trial during wartime;14 and no appellate review by a court, just administrative review by military commanders or the President.15

Col. Zimmermann then went into later changes made to courts-martial procedures (some of them prompted by concerns about the Houston Mutiny trials) beginning with the 1920 Revised Articles of War.16 Under current law, enlisted accused in courts-martial are entitled to a panel of at least one-third enlisted members rather than an all-officer panel.17 Panels in general courts-martial must have at least eight members, and 12 in capital cases.18 A ¾ vote of guilty is required to convict for a life sentence or for 10 or more years imprisonment, and unanimity to impose the death penalty, are also now required.19 Military judges preside over general and special courts-martial since 1968.20 The accused has a right to a free military lawyer in a separate chain of command.21 There are now multiple levels of appellate review, by a JAG officer, the Court of Military Review, the Court of Military Appeals, and the U.S. Supreme Court.22

Heather Kushnerick of the Fred Parks Law Library of the South Texas College of Law (STCL) brought the history of the 3/24th into the present, describing the efforts to correct the injustices of the case and the role of STCL and its law library. Although President Wilson had commuted the sentences of ten of the soldiers to life imprisonment,23 the injustice of the courts-martial remained, with 19 executions and 110 convictions still standing. In October 2020, STCL and the NAACP began work on a petition for clemency for the 110 convicted soldiers based on significant deficiencies in the cases and the unfairness of the proceedings, which was supported by petitions from retired general officers. The Army Board for Correction of Military Records reviewed the records and in May 2022 recommended that the convictions be set aside and that the soldiers’ discharges from military service be characterized as honorable.24 The clemency ceremony was held at the Buffalo Soldiers Museum in Houston on November 13, 2023.25

LLMC Digital, working with the Fred Parks Law Library, digitized the records of the trials obtained from the National Archives and Records Administration in 2009. You can find the records of the Houston Mutiny and Riot at https://cdm16035.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15568coll1/search.

With thanks to Prof. Debbie Harwell, Col. Terri Zimmermann, and Heather Kushnerick for permission and for the use of their presentations from the IALL course, and thanks to the Houston History Research Center for permission to use the photo of an unidentified Buffalo Soldier, item no. MSS0286-0112..

1 Robert V. Haynes, The Houston Riot of 1917: A Tragic Chapter in American Race Relations (Nov. 1, 1995), Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/houston-riot-of-1917; Michael Levenson, Army Overturns Convictions of 110 Black Soldiers Charged in 1917 Riot, N.Y. Times, Nov. 13, 2023,

2 Matthew Crow, Camp Logan 1917: Beyond the Veil of Memory, 14Houston Hist., Spring 2017, at 2-3, available at https://houstonhistorymagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Camp-Logan.pdf

3 Robert V. Haynes, The Houston Mutiny and Riot of 1917, 76Southwestern Hist. Q. 418, 421 (1973).

4 Haynes, Handbook of Texas, supra note 1

5 Crow, supra note 1, at 2.

6 Id. at 5.

7 Id.

8 Haynes, Southwestern Hist. Q, supra note 3, at 438

9 Crow, supra note 1, at 5

10 Manual for Courts-Martial, United States pt. II, ¶6 (1917) [hereinafter 1917 MCM], available at https://www.loc.gov/resource/llmlp.manual-1917/.

11 1917 MCM pt. II, ¶ 7(a).

12 1917 MCM pt. XII, ¶ 295.

13 1917 MCM pt. VII, ¶ 108.

14 1917 MCM pt. VI, ¶ 77.

15 1776 Articles of War, Arts. 46 and 48, reprinted in Manual for Courts-Martial, United States, App. 1 (1917). See also The History of the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals at https://www.jagcnet.army.mil/ACCA.16 See U.S. Dep’t of Army, The Army Lawyer: A History of the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, 1775-1975 136 (1975), available at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/61/The_Army_lawyer_a_history_of_the_Judge_Advocate_General%27s_Corps%2C_1775-1975.pdf.

17 Article 25, Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), available at https://ucmj.us/.

18 Manual for Courts-Martial, United States, R.C.M. 501 (2024), available at https://jsc.defense.gov/Military-Law/Current-Publications-and-Updates/

19 Article 52(b)(1), UCMJ.

20 Art 26, UCMJ; Military Justice Act of 1968 Pub. L. No. 90-632, 70A Stat. 37, available at https://www.congress.gov/90/statute/STATUTE-82/STATUTE-82-Pg1335.pdf.

21 Article 27, UCMJ.

22 Articles 64, 66, 67, and 67(a), UCMJ.

23 President Saves Rioters; Commutes Sentences of Half a Score of Negro Soldiers Convicted of Murder, N.Y. Times, September 5, 1918, at 10.

24 South Texas College of Law Houston, Fred Parks Law Library, Houston Mutiny and Riot Records: About This Collection, https://digitalcollections.stcl.edu/digital/collection/p15568coll1 (last visited Dec. 5, 2025); U.S. Army Public Affairs, Army Sets Aside Convictions of 110 Black Soldiers Convicted in 1917 Houston Riots (Nov. 13, 2023), https://www.army.mil/article/271614/army_sets_aside_convictions_of_110_black_soldiers_convicted_in_1917_houston_riots.

25 Pamela Gibbs-Smith, South Texas College of Law Houston: Camp Logan (June 2024), https://www.stcl.edu/camp-logan/ (last visited Dec. 5, 2025).

This Blog contains entries by members of the International Association of Law Libraries on issues germane to the Association’s areas of focus. Views expressed in an individual entry only represent the views of the author, and not those of the International Association of Law Libraries or the author’s employer.